-

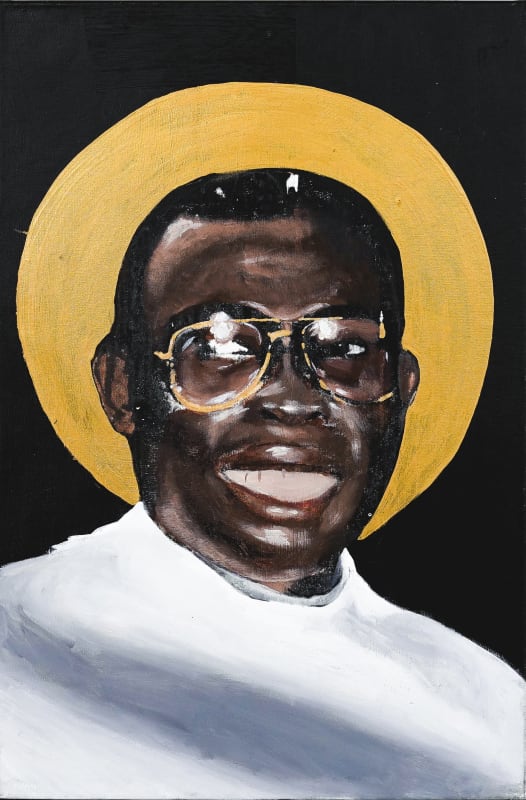

Leonard "Soldier" Iheagwam

-

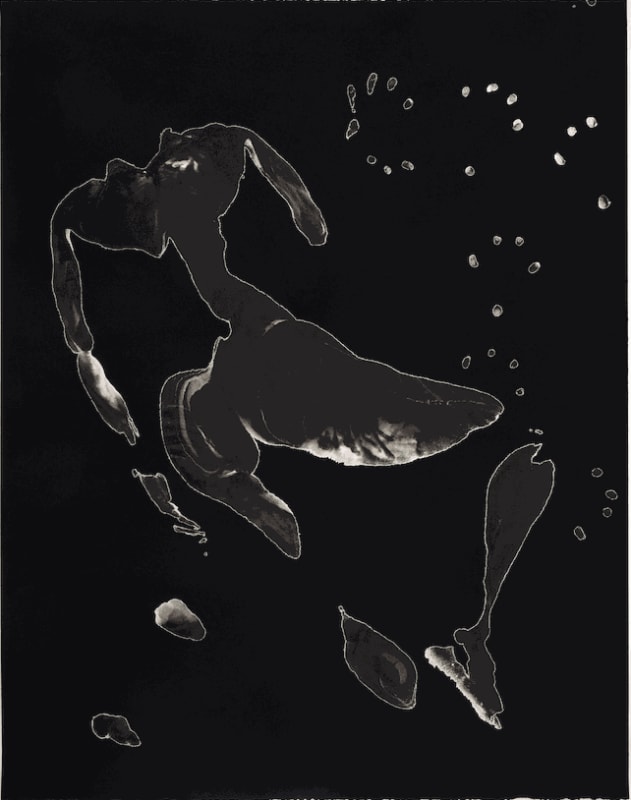

Lucrezia Abatzoglu

-

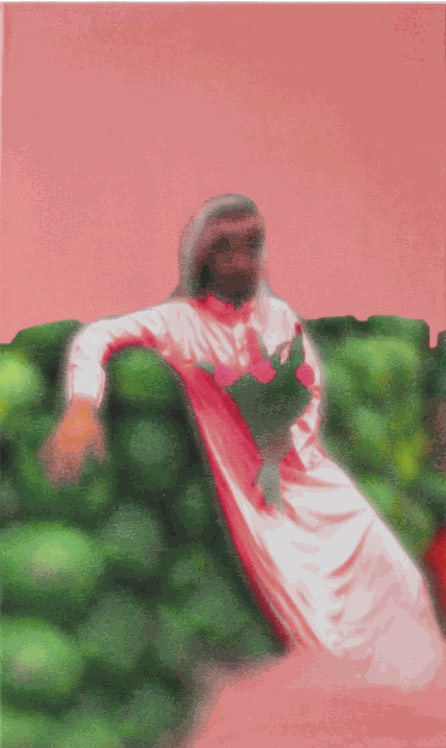

Kesewa Aboah

-

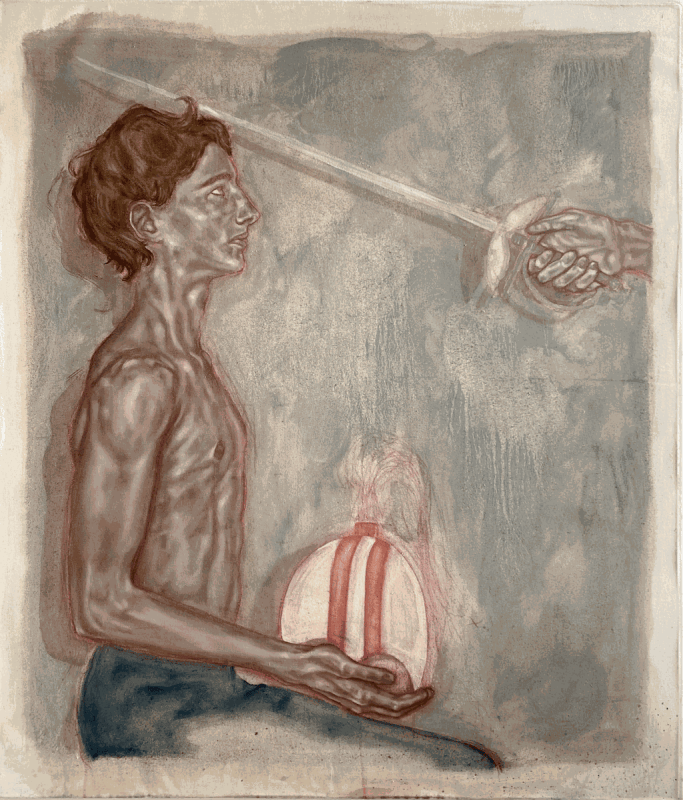

Tamara Al-Mashouk

-

Hawazin Alotaibi

-

Elena Angelini

-

Paul Barlow

-

Fungai Benhura

-

Noah Berrie

-

Alicja Biała

-

Marco Bizzarri

-

Archie Boon

-

Richard Burton

-

Maya Gurung-Russell Campbell

-

Franklin Collins

-

Fleur Dempsey

-

Lucas Dupuy

-

Charlie Gosling

-

Mia Graham

-

Jelly Green

-

Evelina Hägglund

-

Clara Hastrup

-

Antonia Caicedo Holguín

-

Nathalie Hollis

-

Jungwon Jay Hur

-

Frank Kent